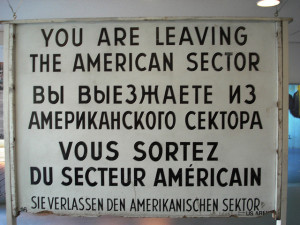

Nineteen forty-five saw the end of an era of open warfare between great powers. It marked the beginning of a new era in which foes would become allies, allies would become foes, and battles would be fought through production, diplomacy, and intelligence services, not by soldiers fighting across remote islands, hedgerow country, or bombed-out cities. The Cold War created new challenges for Western security services in attempting to prevent the Soviet Union from gaining any advantage through espionage. With NSA surveillance coming under increased scrutiny and a new row between Washington and Berlin over spying allegations, are counterintelligence lessons from the Cold War still applicable to today’s world?

Snowden’s Predecessors

If a country wishes to protect itself against the unceasing encroachment of hostile intelligence services, it must do more than keep an eye on foreign travelers crossing its borders, more than placing guards around its “sensitive” areas, more than checking on the loyalty of its employees in sensitive positions. It must also find out what the intelligence services of hostile countries are after, how they are proceeding and what kind of people they are using as agents and who they are.

-Allen Dulles, Former-Director of Central Intelligence, 1963

The first responsibility of counterintelligence is to protect information. If the enemy cannot access information, he cannot obtain it. Passive or defensive measures to protect information can be called “security”. “Physical Security” includes guard forces, protective barriers , flood lighting, intrusion and camera systems, and locking and alarm devices, as well as personnel and material controls such ID cards, passwords, exit controls and access logs. “Information Control” includes items such as security clearances following background inquiries, polygraphs, locking containers, educating staff on security, document tracking, censorship, and coding and encryption.

Though not as glamorous as chasing spies,…after a foreign intelligence agent has successfully penetrated or a domestic colleague has turned inside an organization, security barriers may be the last thing standing in their way.

In 1945, a serving OSS officer found himself reading a report in Amerasia magazine he had written a year before. Upon investigation it was discovered that the publication had been receiving documentation smuggled out of the U.S. State Department. This incident and its aftermath led to a major expansion of the U.S. Bureau of Diplomatic Security under Robert L. Bannerman, including the establishment of a program for “Documentary and Physical Security”. In 1961 the Bureau instituted a standardized system of laminated ID cards in response to the more than 2,000 badges of different types lost by employees over the previous 12 years.

John Anthony Walker, a U.S. Navy COMSEC custodian who sold communications information to Moscow, exhibits why these measures are important. Walker was able not only to get away with selling information he accessed over a period of 22 years, he was so trusted in a system with inadequate information controls and re-investigations that he was given access by others to information he would not otherwise have had—a violation of the “need to know” principle. CIA officer and Soviet spy Aldrich Ames was also granted access by trusting colleagues to information he would not have been entitled to access alone.

Though not as glamorous as chasing spies, erecting physical, procedural and electronic barriers to the access and removal of documents and data is a vital counterintelligence function. Indeed after a foreign intelligence agent has successfully penetrated or a domestic colleague has turned inside an organization, security barriers may be the last thing standing in their way. Today, physical and information security is arguably an even bigger issue considering the amount of data that can be stored on computers or external drives.

There has been an abundance of examples in both the U.S. (see here, here, and here) and UK (see here and here) of government information being compromised, sometimes at cabinet level, by the loss of computers. The cases of Edward Snowden and Private Manning exhibit how much easier the digital age has made leaking, smuggling, and transmitting large amounts of data. Though it isn’t as sexy as spy hunting, the security of intelligence information is as important today, if not more so, as during the Cold War.

There has been an abundance of examples in both the U.S. (see here, here, and here) and UK (see here and here) of government information being compromised, sometimes at cabinet level, by the loss of computers. The cases of Edward Snowden and Private Manning exhibit how much easier the digital age has made leaking, smuggling, and transmitting large amounts of data. Though it isn’t as sexy as spy hunting, the security of intelligence information is as important today, if not more so, as during the Cold War.

Suburban Espionage

Although movies frequently feature embassy break-ins or hunting undercover spies, much of the Cold War spying by the Soviets was done by “legals,” or Soviet citizens or diplomats openly working in the West. Frustrating foreign intelligence operatives is the second major function of counterintelligence and accurate record keeping is the heart of any counterintelligence program. The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in its 1994 investigation into the Ames affair criticized CIA for failing to share counterintelligence records and information within the agency and externally with the FBI and recommended greater cooperation in counterintelligence within the CIA Operations Directorate. As a counterespionage function, it is important to track who visited where and when and how and whom when attempting to identify potential foreign intelligence operatives.

The most effective technique to counter foreign spies is to deny them entry to the country or to expel them if already in place. Throughout the 1960s, the KGB overwhelmed MI5 by placing more agents in London than any other Western capital. In 1971, using fantastical sabotage plans from a KGB defector as a pretext, MI5’s Operation Foot led to expelling 90 Soviet intelligence gatherers and notification of Moscow that an additional 15 would not be allowed re-entry, a setback from which Soviet espionage never recovered. Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB agent who defected to the West, remembered the operation as, “A bombshell . . . an event that shocked the [Moscow] center profoundly.” Eighty suspected Soviet spies were expelled from the U.S. in similar fashion in 1985.

Expelling or excluding foreign intelligence agents causes embarrassment for their masters and ends the career of a covert agent. This is still a tool used today. In 2010, a Russian intelligence officer informed the FBI of a 10-person spy ring, the most famous of whom was Anna Chapman, who became a celebrity upon return to Russia. The U.S. arrested and expelled them in exchange for four agents held by Moscow. Russia attempted to mitigate embarrassment by greeting the exposed spies, who had achieved virtually nothing, as heroes, much as the USSR did following the exchange of Vilyam ‘Abel’ Fisher for F. Gary Powers in 1962.

So why do they spy? A study found that from 1960 money became the most prevalent cited motivation for Americans to become spies, as opposed to ideology, disgruntlement or ingratiation.

Physical surveillance of foreign intelligence operatives has proven effective. There are three general methods: Static surveillance of a known place such as residence or embassy; mobile surveillance by following on foot, by car, or even aircraft, and; electronic surveillance such as phone taps, wireless radio transmitters, mail interception, or geographic tracking devices. A study found that between 1976 and 1991 no less than 16 would-be spies telephoned or walked into the Soviet embassy in the U.S. to sell information and in every case they were caught by FBI surveillance. Cold War history on both sides is rich with such stories. Oleg Penkovsky, perhaps the highest-placed spy the West ever had, was supposedly uncovered through KGB surveillance.

Recent headlines have been filled with controversy over the electronic surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden. The heads of intelligence agencies in the U.S. and UK have responded by publicly discussing how vital the controversial surveillance programs are and claim it has foiled “dozens” of plots. The continuing need to counter electronic surveillance through penetration by foreign governments is shown by constant attacks on U.S. government computers by Chinese government agencies. Though the methods and players have changed with the times after the Cold War, the opponents and counterintelligence requirements remain much the same.

Spies Like Us

There has indeed been exciting episodes in counterespionage history, such as the still-unsettled controversy as to the true allegiances of KGB defectors Anatoli Golitsyn and Yuri Nosenko, leading to equally still-unsettled tales of interrogation, torture, and drugging surrounding CIA and counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton ( see here and here). The difficulty of knowing what the truth is led Angleton himself to refer to counterintelligence as the “hall of mirrors”. Often the most effective sources for uncovering traitors are defected foreign intelligence officers and exploiting mistakes by the traitors themselves. Signals intelligence is another important tool.

Uncovering “moles” is not always exciting. Diligent, plodding deciphering by Meredith Gardner, U.S. Army cryptanalyst, of Soviet signals—the Venona Decrypts—sent from the U.S. to Soviet receivers in 1944/5 led to the unraveling of the Atomic Spy Ring as well as the notorious Cambridge Five network. After years of work, the first Venona breakthrough came with the uncovering of Klaus Fuchs in 1949. Unfortunately, Kim Philby, chief UK intelligence liaison to U.S. intelligence and a Soviet spy, was also reading the decrypts and knew they would soon be on to fellow spy Donald MacLean. Through painstaking work, U.S. counterintelligence narrowed their list. Finally, Gardner connected the dots after deciphering a message that the traitor’s wife was pregnant in 1944, a story that only fit MacLean. This discovery led to the defection of MacLean and Guy Burgess and eventually unraveled the entire ring.

So why do they spy? A study found that from 1960, money became the most widely cited motivation for Americans to become spies, not ideology, disgruntlement, or ingratiation. Aldrich Ames cited “financial pressure” as his initial motivation. A U.S. Intelligence Community study, Project Slammer, interviewed over 30 imprisoned spies. It found they considered themselves “special”, “unique”, and “not a bad person”. Most are anxious or excited by the initial act, giving way to a flourishing relationship with their handlers, finally leading to a stage where they feel remorse and even consider turning themselves in.

During the Cold War, immigrants from the Eastern Bloc were often targeted by Soviet intelligence. This type of targeting continues today. Targeted ethnic recruiting by foreign intelligence services is an issue in counterintelligence that has been seriously hampered by the political and prejudicial connotations associated with it. Intelligence agencies from Korea, China and Israel have attempted to recruit Americans with shared ethnic backgrounds, but mention of this trend elicits protests from organizations representing ethnic communities. The memory of the mass internment of innocent Japanese-Americans during WWII is still alive for many. Nonetheless, states such as China continue to target recruits based on shared ethnicity.

Another study found that late Cold War traitors in the U.S. were often uncovered by electronic surveillance and searches authorised by Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Others were faulty in their tradecraft. Aldrich Ames bought a $540,000 house in cash while only earning $62,000 per year and Robert Haguewood decided to discuss his spying in a bar within earshot of an off-duty cop.

Though the Soviet Union fell in 1991, “moles” remained a concern. In 2001, FBI agent Robert Hanssen was uncovered. After spying for the Soviet Union since 1979, he then offered his services again to Russia after 1991—a total of twenty-two years of espionage. Hanssen was able to evade detection partially because information he compromised was attributed to Aldrich Ames, uncovered in 1994. Hanssen compromised more U.S. intelligence information and assets than any other “defector in place” before him. Angleton’s “hall of mirrors” is still there.

Ich Bin Ein Double-Agent

The West has often had to learn counterintelligence lessons the hard way. But the nature of the study of intelligence is such that one most often only hears of failures and rarely of successes. Intelligence agencies themselves are not alone to blame for counterintelligence failings. Western governments are at a crossroads today regarding the extent of powers of their intelligence agencies and their relationships with one another. Negative public opinion, oft-misleading press reports, and populist politics may lead to the curtailing of electronic surveillance programs, historically among the most effective tools in Western intelligence-gathering.

From the 1945 Amerasia incident to the 2013 Snowden leaks, the security of intelligence information remains a vital concern. The counterespionage function of identifying and countering foreign intelligence operatives, as in the era of the Venona Decrypts and Operation Foot, are just as relevant today, as the case of Anna Chapman and current Russian and Chinese espionage illustrate (and as TV shows like The Americans remind us). The latest fiasco involving the allegations of Washington recruiting a German agent to spy on Berlin may in the short run impair bilateral relations. But this kind of counterintelligence has a long, if checkered, history that should not surprise anyone on either side of the Atlantic. The motivations for turning on one’s own country—money, adventure, ideology, disgruntlement, love, ingratiation—have not changed since the Cold War. Expect future counterespionage escapades to resemble the Cold War past.

Chris Miller is a U.S. Army veteran and Purple Heart recipient following two tours in Baghdad, Iraq and has worked as a military contractor in the Middle East. His work currently focuses on strategic studies. His interests are CBRN, military and veterans issues, the Cold War, and international security affairs.

Chris Miller is a U.S. Army veteran and Purple Heart recipient following two tours in Baghdad, Iraq and has worked as a military contractor in the Middle East. His work currently focuses on strategic studies. His interests are CBRN, military and veterans issues, the Cold War, and international security affairs.

[All photos: Flickr Commons]